The premise behind my being in Wuhan is simple and sound. My earlier sojourn was in Hangzhou —  a town which I really come to like. But it is clearly not your typical Chinese city, nor is Zhejiang University your typical Chinese university. Both are among the elite in their class. If am I to use these post-retirement teaching stints as an opportunity to get to know China, hobnobbing with the elites won’t suffice. I need to mix with the masses. Wuhan fills the bill better.

a town which I really come to like. But it is clearly not your typical Chinese city, nor is Zhejiang University your typical Chinese university. Both are among the elite in their class. If am I to use these post-retirement teaching stints as an opportunity to get to know China, hobnobbing with the elites won’t suffice. I need to mix with the masses. Wuhan fills the bill better.

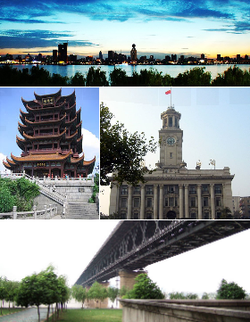

Wuhan is an industrial city that sits astride the mighty Chang Jiang, a few hundred kilometers downstream of the Three Gorges Dam, and at its confluence with the Han River. Indeed, this tributary from the north originally defined three cities: Hanyang, upstream of the Han; Hankou, downstream of it; Wuchang, on the right bank. Altogether, a city of industry and commerce, of about nine million, sitting in the heartland of Han-China.

A city with a gritty past and a grimy present. Following China’s defeat at British hands in the infamous “Second Opium War”, Hubei Province was forced to give “concessions” in Hankou to foreign powers — British, French, Russian. These extra-territorial areas of foreign sovereignty left not only their architectural marks on the Hankou waterfront, but indelible marks of shame in the Chinese collective consciousness.

The oppressors have not all been foreign. In the 1860’s the Taiping Rebels held sway in these parts, but the Heavenly Kingdom of Great Peace wasn’t, and the Qing Imperium exacted its retribution. In 1911 supporters of Sun Yat-sen launched the “Wuchang Uprising”, which ultimately led to the fall of the Qing, but not before some local head-bashing. In the 20’s Guomingdang upstart Wang Jingwei set up shop here in opposition to Chiang Kai-shek, who also wreaked revenge. In 1938 the Japs did a Nanjing-Rape redux, while in 1944 the U.S. firebombed to flush out the Japs. In 1967 the Cultural Revolution unleashed the bloody “Wuhan Incident”. And in between, God himself scourged Wuhan by way of the mighty Yangtze periodically flushing out what was left — all but that sturdy European granite.

Ah, but there have been better times, too. Avid swimmer Mao Zedong braved the River on a few occasions, and even wrote a poem about it in 1956:

I have just drunk the waters of Changsha

And come to eat the fish of Wuchang.

Now I am swimming across the great Yangtze,

Looking afar to the open sky of Chu.

Let the wind blow and waves beat,

Better far than idly strolling in a courtyard.

Today I am at ease.

“It was by a stream that the Master said–

‘Thus do things flow away!’ ”

Sails move with the wind.

Tortoise and Snake are still.

Great plans are afoot:

A bridge will fly to span the north and south,

Turning a deep chasm into a thoroughfare;

Walls of stone will stand upstream to the west

To hold back Wushan’s clouds and rain

Till a smooth lake rises in the narrow gorges.

The mountain goddess if she is still there

Will marvel at a world so changed.

Those promises that “a bridge will fly” and that “walls of stone will stand” were not idle. The “Great Bridge” here is the first to span the Yangtze and thus link northern and southern China with direct rail and road traffic. And the Three Gorges Dam, for better or for worse, is reality.

Truly a city of steel, a Gary, a Cleveland, a Buffalo.

Given this proletarian grittiness, what is there to miss in the teahouses of Hangzhou? In its lakeside promenades where imperial feet once trod? In its tales of butterfly lovers and peony pavillions? Of its fatty Dong-Po pork? Of its lush tea plantations? Of its silks and satins? Of its beautiful women under their parasols? Of its grottoes and temples? Of its pervasive scent of camellia?